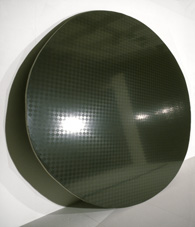

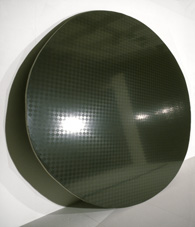

screen, white box, 2000

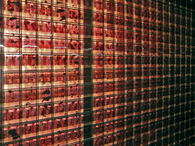

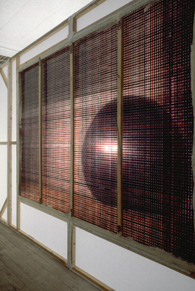

untitled (mad weave), detail, 1995

screen, white box, 2000

one & three states, deitch projects, 2004

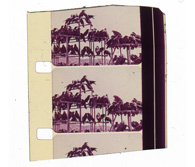

la jetée, south african national gallery, 1997

la jetée, south african national gallery, 1997

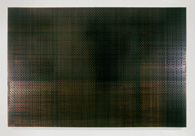

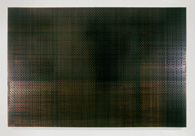

untitled (boogie woogie), detail, 2001

untitled (boogie woogie), white box, 2001

Untitled (Boogie Woogie) is constructed from 1" magnetic film, basically 1980s computer storage film. The film is glossy on one side and matt on the other. This version is the matt side.

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

The first of the "room-within-a-room" installations took place in Richmond, VA in the first incarnation of FLAT International in the US.

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

This panel was woven using 16 mm film purchased from an army surplus supply. The panel is imbedded in a faux-wall and formed part of the Untitled (Richmond VA) display.

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

This panel is constructed using the 1" magnetic film, basically 1980s computer storage film. The film is glossy on one side and matt on the other. This version is the glossy side.

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

elegy, school 33, 1996

Elegy consited of seven unequally sized woven panels in VHS videotape which were lent against the wall. The title is based on Paul Stopforth's work of the same name.

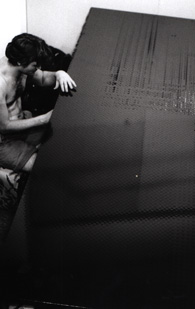

weaving VHS video tape in process, 1996

weaving VHS video tape in process, 1996

untitled (paper), flat international, 1996

The FLAT International show also feated another faux-wall installation. This time one that supported a woven paper piece processed from a large frottage drawing of the studio floor.

untitled (paper), flat international, 1996

untitled (paper), flat international, 1996

untitled (mad weave), 1995

An early version of one of the shaped silhouettes covered with VHS videotape. The weave here is a tri-directional one often reffered to as the 'mad weave'.

untitled (sliver), flat international, 1996

This piece was shown at the FLAT International exhibition and was made with 8 mm videotape.

untitled (sliver), flat international, 1996

silhouettes, durban art gallery, 1994

Silhoettes was the first version of the shaped black forms. Basically a steel frame covered in the case with stretch fabric and not tape.

untitled, 1990

This was the very first woven VHS videotape. A subsequent version of it was constructed for the ICA show in Johannesburg in 1993.

untitled, ica, johannesburg, 1993

|

THE WEAVE OF MEMORY

Siemon Allen's Screen in postapartheid South Africa

by Andrés Mario Zervigón

Art Journal, Spring 2002 [extract]

Approaching the recent work of South African artist Siemon Allen is like encountering an object of classic Minimalism. His shiny black behemoth entitled Screen (2000), for example, bears a close resemblance to Tony Smith's Die of 1962. And like Die, whose enormous size, heavy dark rolled steel, and name all suggest a lethal threat, Screen also appears to mean something beyond its mere physical presence. [1] Perhaps its primary material, woven VHS videotape sectioned into twelve panels, contributes to this nonspecific sense of meaning. Or maybe its imposing size, the fact that most viewers cannot peer inside its six-foot walls, and the feeling that one can only guess at the recorded content of its constituent material, all contribute to this vague impression that Screen bears meaning of great significance. Indeed, the very fact that the work offers numerous levels of opacity may alone generate its greatest single message, its demonstrative unwillingness to reveal its contents.

For the last seven years, the international art world has fixed its attention on South Africa's art scene and has found itself fascinated by the country's sophisticated output. [2] Many foreign observers have been thrilled to see that contemporary art can successfully negotiate a history and context resonating with the social gravity of South Africa's transition from apartheid. [3] Indeed, much of the country's art revisits the apartheid past in provocative ways, mining South Africa's material history like an archive of memories and re-presenting this archive's contents for careful consideration. Allen's Screen, however, stands strangely apart from this trend in art. Rather than present discomforting terms of the past for reevaluation, Screen purposefully withholds its archived contents. The VHS videotape, which is normally used to record personal experiences, surveillance, or news, here reveals nothing apart from its shiny surface and the viewer's reflection in that surface. As videotape, Screen offers a material term for memory even as its black opacity references that memory's utter inaccessibility, the same sort of memory other South African artists labor to recoup. Indeed, the very weave of Allen's Screen offers a metaphor for the integration of individual memories into one national history, yet, simultaneously, the weave's tightness denies any simple decoding of that memory by, for example, feeding the tape through a video player.

In a sense, Screen functions apart from the country's archive-based art as an antimemorial, quite literally reflecting South Africa but otherwise refusing the memory its component material evokes. Like that of the country itself, Screen's memory has yet to be determined. It is precisely in this space between the self and external reference, in the vague meaning navigated by Allen's almost-Minimalism, where Screen operates so successfully For in the context of post-apartheid South Africa, where the stakes for representation remain high, a work of art that makes the mechanics and deferral of reference its primary concerns necessarily highlights the process, rather than the terms, through which a nation renegotiates its past.

This distinction is significant. South Africa has spent the past seven years heavily engaged with its past, often producing in the process as much divisiveness as reconciliation. This fact became painfully apparent at hearings before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Established in negotiations between the last apartheid government and the African National Congress (ANC), the TRC was charged with uncovering the truth of apartheid-era crimes in exchange for their perpetrators' general amnesty, an arrangement that granted judgment for these crimes to the country's diverse citizens and, ultimately, to history itself By taking this course, South Africa had essentially chosen to represent its past rather than avenge it. And indeed, the TRC's creators hoped that this re-presentation, this disclosure of crimes to broad public scrutiny absent institutional judgment, might elicit a broad consensus on the past and thereby promote the kind of reconciliation a successful future demanded. But once it was seated, the commission sometimes took on a circuslike quality, threatening to render such collective judgment far more difficult than initially planned. [4] Dramatic confessions and horrific memories broadcast around the country quickly excited a mass audience whose diversity of responses often served to heighten, rather than resolve, the nation's differences. Because the past meant vastly different things to different people, its terms were difficult to digest collectively. [5]

The ambivalence produced upon uncovering South Africa's past typifies the country's general rapprochement with history. Unsurprisingly, many of its artists have elicited similarly mixed emotions as they, too, journey through the past, re-presenting familiar cultural terms without casting any obvious judgment on those terms' meaning or significance. As with the TRC, this art of memory has often found itself heightening, rather than soothing, the contentiousness of South Africa's history The fight generated by the confessions and pardon of the murderers of political activist Steven Biko, for example, found its equivalent in a heated debate about the use among white artists of the black female image. [6] Reconciliation, as it turns out, requires the kind of shared memories and values that apartheid specifically sought to extinguish. How, then, can such values be determined in contemporary South Africa when the existing terms by which they are generated often serve to heighten and spectacularize difference? Indeed, can the country ever commemorate its history? The answer to this question may unfold only over the course of decades, but Allen's Screen proposes a number of interesting provisional responses. As in many other South African contemporary art works, his structure takes memory as its central concern, yet unlike these other works, it does so without outlining that memory's contents. The very opacity of his woven tape suggests that memory can be decoded only once consensus arises on how it will be read. Screen, therefore, memorializes memory by making its indecipherability, rather than its contents, a central aesthetic focus.

Such a strategy can only find success in an environment where memory's terms are actively contested. This is why phenomena such as the TRC and archive-based works of art are so important to the success of Allen's structure. These same phenomena, however, can be troublesome in a way that Allen's Screen is not. Generally in South Africa, images have long borne significant consequences precisely because their power and meaning have never been negotiated properly. During the apartheid era, they helped mediate to a larger public an official understanding of race, and they even participated in the most basic applications of minority power. The notorious passbooks blacks were required to carry, for instance, bore the carrier's photographic portrait. Such fusing of image with legal pass linked the representation of black identity to its effective criminalization. Other images produced by the everyday culture of apartheid, as in television and advertising, also circulated within a context resonating with Group Areas legislation, resettlement schemes, and Bantu education policies, the dominant instruments of racialized power that institutionally defined the country's discourse on race. Within this environment, both the creation and the reception of representation were inevitably determined by the dominant racial structure. Such was the case even when images intentionally resisted apartheid's discourse, for the singular focus of this opposition only seemed to confirm the racial discourse's dominance. Inevitably, apartheid transformed any image into yet another mediator of racial meaning and, thereby, another tool of that oppressive system's power.

Today in South Africa, images remain haunted by their previous use even while charged with their new task of renegotiating identity. Whether they appear in soap operas broadcast on reformed television networks, advertisements found in glossy magazines, posters used in political campaigns, or the news, South Africa's new images inevitably retrieve the past even as they mediate visions of a "rainbow" future. [7] A popular soap opera portraying a black middle-class family's integration into Johannesburg's plush northern suburbs may help establish a new understanding of identity, but it does so against a past when blacks only cleaned and gardened in this area. [8] Its representation of race must therefore remain in dialogue with terms of the past if only to acknowledge contrasting understandings of race and separation.

The danger posed by this dialogue is that an image circulating in contemporary South Africa may not be able to critique its previous power without also purveying it, even spectacularizing it, depending on the viewer being engaged. This, in turn, is precisely the danger faced by South African artists who try to reconcile the past through a use of images retrieved from their country's visual archive.

[...]

But does this yard sale of memory initiate a discourse on South Africa's recent history, or does it constitute nostalgia for the country's first phase of transition, an uncritical retrieval of the terms yet to be accepted? Although allegorical, procedures such as [Senzeni] Marasela's and [Penny] Siopis' allow any number of objects to stand for infinitely shifting ideas, they do not necessarily foreground the process of association through which representation's meaning and power arise. The same might be said of Bridget Baker's sweaters, Mbongeni Richman Buthelezi's compositions of melted shopping bags, Willie Bester's mechanical assemblages, and Gavin Younge's vellum collections, all of which sensitively prepare a renegotiation of the past through a disgorging of that past's contents, What they may lack, if we do find such representation of memory spectacular, is what Allen provides, the screen on which memory must be projected. [12] By referencing memory through an opacity yet to be deciphered, Screen elliptically evokes both the country's past and its deferred reconciliation, absent the spectacular. And this is exactly where the sense that Screen means something significant plays a role. Within the South African context, where history constitutes the country's primary discourse, Screen's videotape is far more likely to be understood as a general reference to national memory. [13] This possibility suggests that a consensus on historical meaning remains possible in South Africa despite its citizens' diverse experience of the past. Screen elicits a practice in consensus precisely because it resists the contested terms through which this past is normally articulated.

Like other conceptual works of art in which object and idea are unhinged, Screen allows its components to allude to any number of shifting concepts. But unlike pieces such as Marasela's and Siopis', which appropriate images and materials already rich in their own meanings, Allen's tape consistently turns back to its own opacity and indecipherability. It becomes a near free-floating signifier, capable of enabling almost any association the viewer might make. Does the tape signify its recorded content at all, or does it refer to the industry of surveillance built under the apartheid regime? Perhaps the second option would strike South African viewers first, considering a recent series of revelations. Two years ago, a number of "training" videotapes were discovered that showed white South African police officers setting their attack dogs on undocumented Mozambican immigrants. The tapes had supposedly been used to teach the training of attack dogs, but instead the police distributed copies for their own personal amusement. The recorded attacks were particularly brutal and left their Mozambican subjects seriously disfigured, a fact that makes their use as entertainment all the more disturbing. This discovery revealed the surviving brutality of a supposedly expired apartheid period. Such revelations clearly give videotape an unsettling association for the everyday South African.

Or, rather than alluding to these gruesome events themselves, perhaps Allen's tape refers to the TRC hearings before which similar revelations were largely made. Indeed, the TRC recorded all its hearings and often broadcast its gripping footage to the entire country Maybe Screen evokes the abundance of these recordings, their dissemination over television, or even the popular culture that mediated their meaning. Allen prefers to keep this signifier as free as possible, refusing to reveal what lies recorded on the tape's surface except, on occasion and with deceptive frivolity, to suggest Princess Diana's funeral as its content. This statement confuses Screen's darkly serious reference yet suggests its status as a memorial.

Most important, Screen offers an alternative Minimalism of self-reference and external reference, and a liminal space between the two, where the motivation of meaning itself becomes the subject of aesthetic inquiry Yet the fact that Allen's work successfully employs the formal rhetoric of Western Minimalism should not distract from its significance as a South African work of craft, a weave. This, too, contributes strongly to the work's referential power. The positive associations produced by a work that could be viewed simultaneously as craft and as fine art first occurred to Allen in 1989, well before South Africa saw the political and cultural developments with which his new work dialogues. Then a sculpture student at Durban's Natal Technikon art school, Allen also studied weaving with the Zulu artist Sam Ntshangase. Rather than teach the traditional craft, however, Ntshangase encouraged his students to disassociate weaving from the fabrics with which it is normally linked. Taking this lesson to its logical end, Allen began making large four-by-eight-foot weaves of shredded Coke cans, movie film, videotape, and even ripped-up painting canvas. He exhibited the weaves as framed two-dimensional works, thereby encouraging them to be viewed as painting. Yet, as weaves produced through painstaking labor, they also beckoned to be seen as craft. In addition, their incorporation of nontraditional materials seemed to stress a sculptural presence. These formal dislocations powerfully blurred the divisions of craft and fine art into which African and Western art, respectively, have customarily been separated. But of equal significance, they also interrogated Western distinctions between painting and sculpture. Through the adoption of such formal boundary breaking, Allen's early weaves established a dialogue between South Africa's cultural traditions and the type of avant-garde gesture whose heritage lay in places like Paris and New York.

While Allen's weaves seemed of limited relevance to the more activist and content-driven art preferred by socially conscious artists during apartheid, their potential cultural resonance changed with apartheid's twilight. [15] In late 1993, eight months prior to the country's first democratic election, Allen cofounded an alternative gallery with fellow recent graduates. In the spirit of the approaching transition, these artists felt enough freedom from government restrictions to establish an experimental space where, as Allen recalls, "anyone could do anything." (16) Housed in their cooperative apartment, or flat, the FLAT gallery essentially sought to transform Durban's long-dormant art scene by selectively adopting Western avant-garde precedents from which South Africans had long remained isolated. Combined with the excitement of apartheid's end, this engagement with Western culture served to produce an art that was both aesthetically and politically radical. Suddenly, Allen's weaving practice seemed presci ent, gently engaging African and Western aesthetic traditions, and serving as a foil to themes broached by the FLAT's other, frequently more assertive, exhibited works.

[...]

In the midst of this experimentation with avant-garde precedents, Ntshangase became a semipermanent resident at the FLAT and was thereby able to provide Allen with fresh inspiration and encouragement. As a cofounder of, and participant in, the FLAT, Allen had already begun experimenting with magnetic audiotape, recording readings and exhibition discussions, which he later played back during the shows themselves. It was not long before he began using this tape as raw weaving material as well. The small format of audiotape, however, proved unwieldy in the weaving process, and he returned to videotape. At this point, he began exhibiting his video weaves not only as independent works, but also within larger three-dimensional assemblages. He constructed rooms out of wooden frames and white cloth, and in these mock galleries the weaves hung like strange voids. In these pieces, he highlighted the craft basis of his art by, for example, using cross-weaves whose diamond-shape patterns mimicked the look of cloth far more directly than Screen's square weave would. As a consequence, a viewer confronting the panels of a structure such as his Untitled (Richmond, VA) (1996) might gain the impression of looking at a painting or textile, both of which referenced the country's multiple aesthetic traditions. Allen's art literally wove African and Western aesthetic traditions together while leaving the significance of this interaction open to the intersubjective consensus of its viewers.

Allen's new work embraces Minimalism more tightly than his FLAT-era pieces had, yet the significance of its basis in craft continues to resonate with local artistic traditions. Now dialoguing with an art rooted in recollection, his increasingly inaccessible weaves suggest that South Africa's memory should never be fixed in a national representation at all but should continue being represented by the country's typically hybridized forms. Ultimately, as both a critique of and a stimulus to representation, Screen demonstrates the limits and advantages of South Africa's fascination with its own memory.

Andres Mario Zervigon is an assistant professor of art history at the University of La Verne, California. He is currently working on a reappraisal of John Heartfield's photomontage practice.

view full article

I would like to acknowledge Siemon Allen for his generous assistance n the writing of this article. I owe many thanks as well to Charlotte Eyerman, Amy Lyford, Timothy Rohan, and Lauri Firstenberg, all of whom provided critical feedback on the project.

[1.] American Minimalist works were often interpreted as referring to nothing more than their literal presence. Die represents an early exception to this interpretation. For a discussion of Smith's Die within the larger context of Minimalism, see James Meyer, ed., Minimalism (London: Phaidon Press. 2000), 12-45.

[2.] The fascination with South Africa's contemporary art followed a general interest in the country's transformation to democracy. The first Johannesburg Biennial, held in 1995, offered the first broad exposure of the country's art to an international audience, Subsequent discussion was ratcheted up by the even more comprehensive 1997 Johannesburg Biennial, an exhibition of William Kentridge's art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1999), and various shows of contemporary South African art, for example, Liberated Voices (1999) at New York's Museum for African Art. South Africa's recent art has also hit New York's Chelsea gallery scene. A particularly exciting exhibition, Translation/Seduction/Displacement, highlighting precisely how sophisticated this art has become, was staged at the White Box Gallery in March 2000. This is where I encountered Allen's Screen,

[3.] This was particularly evident in the show Liberated Voices (see n. 2).

[4.] American audiences can observe the character of the TRC hearings in the documentary film Long Night's Journey into Day (2000), directed by Frances Reid and Deborah Hoffman.

[5.] For a critical discussion of this problem see Brandon Hamber, From Truth to Transformation; The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa (Braamfontein: Catholic Institute for International Relations, n.d.), 1-28.

[6.] Okwui Enwezor initiated this debate with his article "Reframing the Black Subject: Ideology and Fantasy in Contemporary South African Representation," Third Text 40 (1997), 21-40. He suggested that rather than renegotiating identity, the work of some South African artists was instead recycling old racial conceits through representations of the black female body. He voiced particular concern for the montages of Penny Siopis and Candice Breitz, visually disjunctive works that seemed to render the black body abject and docile. The response among South African artists was largely hostile, particularly because Enwezor was then curating the 1997 Johannesburg Biennial. International curators, concluded many of these artists, could not truly understand South African art and certainly should not cast aspersions on it. Equally interesting was the debate among South African artists themselves on representing across racial lines. It seemed clear from the debate that a neutral image for one South African could constitute a terrible affront to another (this observation is based partly on a discussion I had with Allen in December 2000). Other responses appeared in Third Text, an interesting example being Brian Keith Axel's "Disembodiment and the Total Body. A Response to Enwezor on Contemporary South African Representation," Third Text, 44 (1998), 3-16. [see also Grey Areas, edited by Candice Breitz and Brenda Atkinson]

[7.] This is the term adopted by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and, subsequently, the new government to stress a diverse nation of equals.

[...]

[12.] Indeed, many of Allen's other works reveal this fascination with the archive, offering a dialogue between memory and its terms within his own oeuvre. All merit extended discussion as well; they include Stamp Collection: Imaging South Africa (2001) and the highly conceptual Zulu far Medics (1994).

[13.] Allen has exhibited his two most recent video weaves in New York at the White Box Gallery in Chelsea, in March 2000 and March 2001. Both exhibitions focused exclusively on South African art. Although all of the works selected serve their South African constituency on fascinating aesthetic and social levels, I would maintain that within the context of a specifically South African art show, they function similarly for American audiences, particularly given our similar histories. Allen has remarked that when his Untitled (Richmond, VA) (1996) was originally exhibited outside the context of South African art, it resonated far differently, even rather flatly.

[14.] This event is not as remote from the country as one might think, At the time of Diana's death, her brother, Charles, the ninth Earl Spencer, was living in South Africa.

[15.] For further information on South African art in the apartheid era, see Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa (Cape Town: Catholic Institute for International Relations, 1989) and Gavin Younge, Art of the South African Townships (New York: Rizzoli, 1988).

[16.] This was the agreement made among the group's founding members. Siemon Allen, the FLAT Gallery, unpublished manuscript, 280.

[17.] Allen exhibited his two most recent weaves. outside South Africa. Both exhibitions were held at the White Box Gallery in March 2000 and March 2001, and focused exclusively on South African art. I would maintain that within such a setting, his recent weaves continue to speak to a postapartheid context in spice of their geographic dislocation, Indeed, Americans may gain particular insight into this dialogue considering the similarity our history maintains with South Africa's.

|

untitled, anderson gallery, 1996

untitled (richmond va), flat international, 1996

translation/seduction/displacement catalog

after the diagram, invite, 2001

the birds, offcut, 2008

the birds, offcut, 2008

|

EXHIBITION HISTORY

ICA

Siemon Allen, Greg Streak

November 14 - December 5, 1993

Institute of Contempoarary Art, Johannesburg, South Africa

VITA 93

May 10 - July 24, 1994

Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

FLAT

Ledelle Moe, Thomas Barry, Nkosinathi Gumede, Carol Gainer, Adrian Hermanides & Siemon Allen

March 5, 1994

FLAT Gallery, Durban, South Africa

ARTISTS INVITE ARTISTS

Silhouettes

November 1994

Durban Art Gallery, Durban, South Africa

UNTITLED

Untitled (Richmond, VA)

1996

FLAT International, Richmond, VA, USA

ARTSITES 96

Elegy

June - July, 1996

School 33, Baltimore, MD, USA

2ND JOHANNESBURG BIENNALE

curated by Okwui Enwezor

GRAFT

curated by Colin Richards

La jetée

October 12, 1997 - January 18, 1998

South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

TRANSLATION/SEDUCTION/DISPLACEMENT

curated by Lauri Firstenberg & John Peffer

Screen

February 3 - April 1, 2000

White Box, New York, NY, USA

AFTER THE DIAGRAM

curated by Lauri Firstenberg & Douglas Cooper

Untitled (Boogie Woogie)

April 26 - June 2, 2001

White Box, New York, NY, USA

FREEDOM SALON

curated by Christina Kukielski and Apsara DiQuinzio

One & Three States

August 28 - September 4, 2004

Deitch Projects, New York, NY, USA

LIGHT SHOW

curated by Henrietta Hamilton, Robert Fraser & Vaughn Sadie.

The Birds

with Siemon Allen, Stephen Hobbs, Simon Jaques, Vaugn Sadie, Greg Streak, Bronwen Vaughn-Evans, Jeremy Wafer, James Webb

January 24 - February 21, 2008

BANK Gallery, Durban, South Africa

MONOMANIA

curated by Storm Janse van Rensburg

The Birds

with Siemon Allen, Ryan Arenson, Joanne Bloch, David Koloane, Arie Kuijers

August 7 - September 6, 2008

Goodman Gallery Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

DISTURBANCE - CONTEMPORARY ART FROM SCANDINAVIA AND SOUTH AFRICA

curated by Maria Fidel Regueros, Clive Kellner

The Birds

with Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Siemon Allen, Bodil Furu, Veli Grano, Marja Helander, Nicholas Hloba, Astrid Kruse Jensen, Alastair McLachlan, Nandipha Mntambo, Anthea Moys, Mika Ronkainen, Athi Patra-Ruga, Maia Urstad, James Webb

October 26, 2008 - March 1, 2009

Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

IMAGING SOUTH AFRICA: Collection Projects By Siemon Allen

Screen II

curated by Ashley Kistler

August 27 - October 31, 2010

Anderson Gallery, Richmond, VA

|