advertisement, art south africa, 2009

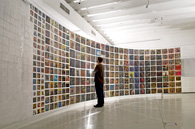

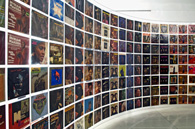

covers from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

stamp collection, durban art gallery, 2009

newspapers, durban art gallery, 2009

better, bank gallery, 2009

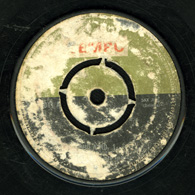

large prints, bank gallery, 2009

better, bank gallery, 2009

makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

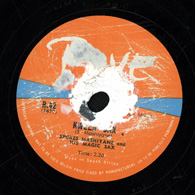

labels from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

newspapers, durban art gallery, 2009

ipod from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

rave, detail, bank gallery, 2009

covers from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

covers from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

map from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

map from makeba!, bank gallery, 2009

large prints, bank gallery, 2009

tempo, detail, bank gallery, 2009

newspapers, durban art gallery, 2009

|

IMAGING SOUTH AFRICA: RECORDS|NEWSPAPERS|STAMPS

BANK Gallery, Durban South Africa

March 3 - April 16, 2009

Durban Art Gallery, Durban, South Africa

March 8 - April 26, 2009

ARCHIVING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA OUTSIDE OF ITSELF

Three concurrent installations

Historically the act of archiving has been regarded as objective and neutral. However, currently this definition has come under scrutiny and the ways in which we define ‘the archive’ more rigorously considered. In examining a collection of artifacts, for example, we now not only ask about the nature of what is being collected, but also who is doing the collecting and with what kind of framing is the material presented. We consider what kind of information is carried in the collected material, and in doing so look both at that which is explicitly shown within a collection of archival materials, and perhaps more importantly what is not. Every object in an archive is a piece of incomplete history; every collection of these objects the result of selection and framing. For the past ten years I have been exploring aspects of the archive through a series of works that include projects using ongoing collections of newspapers, postal stamps, trading cards and audio recordings.

In my earliest collected artifacts pieces: The Hardy Boys, Stamps, and Shirt ‘n Boots I examined and critiqued an internal construction of self image, in my case, identifiers specific to an adolescent white South African male. In these works, intentionally narrow in scope, I presented artifacts from my own youth, and in doing so addressed the limitations of South African culture as experienced through the lens of a particular and individual experience.

With Stamp Collection, the first of the large-scale collection projects, I continued this examination of an internally constructed image, moving the focus from ‘self’ to ‘nation’. Stamp Collection, an ongoing collection of over 23 000 South African stamps from 1910 to current was displayed in a variety of ways including massive grids and timelines with text. Stamp Collection presents a history of South Africa. But this is only a partial history. The stamp is an official image constructed by the issuing government; one that reflects the way in which that government wishes to define or ‘image’ itself. The ubiquitous postal stamp is an example of pure propaganda spread through a very unique kind of currency both countrywide and globally. Also, in the secondary market, philatelists, worldwide, in collecting stamps expand these channels of dissemination.

While Stamp Collection shows an internally constructed image, Newspapers and Records are archive projects that show an external construction of image.

Newspapers is a collection of newspapers from various US cities where any mention of South Africa has been isolated and highlighted with cut out windows in overlaid tracing paper sheets. The result is a framing of both articles and single sentences or phrases. This collection project examines how the US media represents South Africa, and in doing so offers what might be seen as a look at what is an externally constructed image. The project reveals editorial decision making on what is viable content for an American audience on the subject of South Africa and asks “How is South Africa perceived through the prism of the US press?”

Records the most current of the collection projects is a massive archive of South African audio material. This ongoing project, currently evolving into a web based audio resource includes the work titled Makeba!, an almost comprehensive collection of the exiled South African singer’s recordings released internationally in the form of vinyl, tapes and CDs, and specifically targeting similar recordings pressed in multiple countries.

Records began when I came across one of Makeba’s early records (1965) in a thrift store in the United States. After reading the text on the cover I was struck by the political nature of its message and became interested in how in the simple act of listening to a piece of music a listener might be made aware of South African political issues. Also of interest to me was the fact that the audio medium was itself instrumental in the distribution of the anti-apartheid message internationally and, perhaps ironically, how the commodity culture of the music industry might become the distributor of a political message and in doing so be an agent of change.

Though Makeba and her music are well known worldwide, her exile and subsequent banning in South Africa meant that a large portion of her work remained unavailable in her home country during many of her most productive years. Even in post-apartheid South Africa many South Africans, especially young people, seem unfamiliar with Makeba and her work. As a result, not surprisingly, most of the Makeba recordings in my collection were acquired outside South Africa. The Makeba archive in this way becomes a kind of tracing of the global journey the voice of Makeba has taken.

The larger project Records, actually developed quite naturally out of the compilation of the Makeba archive. In seeking out Makeba records in stores overseas and on eBay, I came across numerous other South African recordings and became interested in expanding this audio history. Both archives have been compiled using the global market of eBay, and indeed most of the records in the collections were acquired internationally. Interestingly very few recordings of South African music in the collection were acquired in South Africa. The reach of the recorded material archive is global. For example, recordings from South Africa or by South African artists in exile have been found all over the world from a remarkable range of countries including Japan, Israel, Turkey, and Argentina. Using the web as a resource and in Records as a site of presentation my intention is to construct a comprehensive archive of South African audio. Unlike Stamps, Newspapers, Cards, and Makeba!, where display is central to the concept of the work, Records, which includes early township jazz, Afrikaner folk songs, political speeches and audio art, will operate ultimately as a web-based archive, a resource of South African audio history.

All of my collection projects began with an examination of an internal construction of image. The first were personal items and reflected the notion of constructed personal identity. The Stamp Collection explored aspects of how South Africa viewed or attempted to view itself through an enormously varied mass of readable images. Newspapers explored aspects of how the image of South Africa was constructed externally in the US media. Records deals with a kind of diaspora ofthe South African recorded voice.

With the development of these projects over the past ten years has come the realization that they are all linked by a collector who works outside of South Africa. These collections are made up of South African artifacts acquired from international sources. In examining images of South Africa constructed by others outside of the country, the collection projects have become, as impossible as it might seem, an attempt to archive a history of South Africa outside of itself.

Stamps & Newspapers at the DURBAN ART GALLERY

Durban Art Gallery, a museum which includes both a significant collection of South African Art and a long history of support for African Art, is a colonial building located in old downtown Durban. Here were shown Stamp Collection and Newspapers.

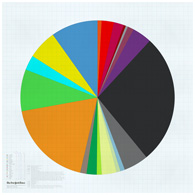

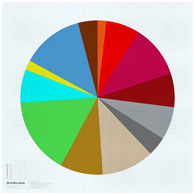

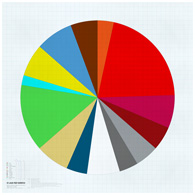

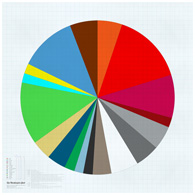

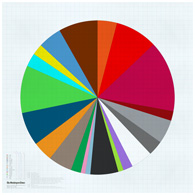

Given that Newspapers presents an image constructed external to South Africa, in this case through the US Press and Stamps an image constructed internally by the South African government, in the separate rooms of the Durban Art Gallery, the two collections seemed to sit in counterpoint one to the other. Newspapers were presented in the larger open circular gallery, the installation configured in such a way that each wall section in the space held the newspapers of an individual American city—The New York Times, The St. Louis Post Dispatch, The Des Moines Register, The Washington Post and The Washington Times, with a section for display of the research graphs showing a analysis of content by topic from the ‘framed’ articles.

The installation consisted of panels that attached to the walls with the newspapers pinned to these panels. Each newspaper was covered by a thin sheet of tracing paper that resulted in a semi-transparent overlay with a cut out where the article about South Africa was located. From across the room, the work appeared as a large grid with subtle shifts of grey and small patches of color. Up close the articles were easily read and the variety and revealing nature of this ‘external’ construction of image accessed.

The newspaper collection not only fits formally in the space, but corresponded conceptually to the massive space. The grand scale, the notion of global media as ‘showing light on matters’ and outward looking were reinforced emotionally by the large circular sky-lit space.

In contrast, the logical conceptual counterpoint to the newspaper collection, the stamp collection, was presented in the smaller, darker “project room” just adjacent to the circular gallery. The outwardly facing display of the newspapers in the large, open space contrasted with the more introspective archival stamp collection in a darker room. The project room was fitting for a work referencing the more precious intimate act of stamp collecting.

Records at BANK GALLERY

In the main gallery space were three large works—Covers, Labels and Map—developed out of the most recent collection in the Records archive, Makeba! On one wall was a floor to ceiling massive grid showing digital photographs of record labels. On the back wall was a massive map charting the movements of the recordings from production site to country where the item was ultimately acquired, bringing into focus the notion of how through the voice and iconic presence of Makeba the image of South Africa traveled globally. On a curved wall made with vinyl sleeves in the center of the room LPs, EPs, and CDs from the entire Makeba collection were inserted to show front cover art and back cover text.

Records also included three large prints of single records taken from the larger archive: Better, Rave and Tempo. These prints were not part of the Makeba! project but did develop out of it. They were presented in a separate space at the rear of the Gallery.

The prints were detailed scanned enlargements of individual records with detail showing scratches and chips on grooves and labels. The image in the print captured not only the historical audio visually in the form of the lines or grooves, but also the scratches, damage, and repair work done by subsequent owners, which was clearly visible.

Records on the INTERNET

The ultimate venue for the full archive of the South African audio materials would be an audio archive on the web. Rather than operating as a display this collection would be an accessible archive where site visitors could search, view original packaging, and possibly listen to audio clips.

SIEMON ALLEN, 2008

|

stamp collection, durban art gallery, 2009

stamp collection, durban art gallery, 2009

stamp collection, durban art gallery, 2009

nyt research, durban art gallery, 2009

dmr research, durban art gallery, 2009

stl research, durban art gallery, 2009

wp research, durban art gallery, 2009

wt research, durban art gallery, 2009

|

"THE COLLECTOR"

review by

PETER MACHEN

from the Weekend Witness, Pietermaritburg, South Africa

March 21, 2009

Siemon Allen is more than a little obsessive. The word might have negative connotations for some, but it's an essential element of being a collector and an archiver. Allen, who is principally an artist, has managed to turn a fetish for collecting into vast artistic projects. A graduate of Durban's DUT, he has been living in the United States for the last 13 years and has, for the last eight years, been exploring the. image of South Africa through collections of stamps, newspapers and records.

Operating from his external vantage point, Allen has been systematically accumulating these mass-produced objects, which he meticulously catalogues and displays in large installations that take up entire gallery spaces but that could also be compressed into a few cardboard boxes.

Allen is in Durban to show three of his collection projects "Stamps", "Newspapers" and "Records" - and his gently insistent integrity is reflected in these large bodies of work, which have already been exhibited widely in the U.S. in such prestigious spaces as the Whitney Museum. This is the first time that the three projects, which form part of a larger project called "Imaging South Africa", have been brought together and shown in South Africa.

And although Allen has been back to the country in recent years, this return, together with the three exhibitions, feels like a homecoming. The fact that "Records" is currently installed in Florida Road's Bank

Gallery has a particular resonance as Allen lived in the building next door when he was a child and worked in the gallery building when it was still a bank that his mother managed. (The other two elements of "Imaging South Africa" are on show at the Durban Art Gallery.)

The three exhibitions, both individually and collectively, verge on the monolithic. They also, should you be so inclined, pose heavily layered questions about what art is and isn't. This ever present albatross weighs heavily on our conversation, and while there's a level at which Allen really doesn't care whether it's art or not – because he's doing what he wants to do and he's exhibiting the results in a gallery - it is at the same time a concern that preoccupies him during the course of conversation. But the preoccupation is pedantic rather than central, and far more important is the political nature of the work.

"Newspapers" is obviously so, cataloguing mentions of South Africa in five American newspapers over the course of eight years.

"Stamps" - which includes stamps from a century ago to the present - catalogues the way in which a country presents itself to the world in a thumbnail formalism.

"Records" includes the covers of all the vinyl records and CDs that Miriam Makeba produced in her lifetime; Makeba is herself a potent political figure.

Allen's collections function on many different layers, but there are two discreet levels to the work. The first is the act of collecting or archiving. The other is in the presentation of the work, in which the collections are shaped into large-scale objects that abstract through aggregation into a high modernism, calling to mind specifically the work of Mondrian, but also all of the arguments around modernism and its impact on the 20th century. The rows of stamps might reduce to blocks of modernist colour when you step back from them, but they also echo the infinite repetition of the office cubicle and the structure of skyscraper cities built out of glass and metal.

But are these modernist structures that house the works little more than a clever trick to elevate collections or archives to the status of art? I ask Allen the question as a devil's advocate, but he has his own devil sitting on his shoulder, and he never answers the question concretely, turning it into a discussion that meanders through the rest of our conversation. And again the question is perhaps more interesting than it is important.

There is something else, though, that is the passion behind obsession. It's something that oddly enough didn't come up in the course of our conversation - which lasted hours beyond my 3D-minute Dictaphone tape and included a quick dinner at Spiga D'Oro - but that tinged every word spoken. And it's true that there is something that transcends materialism in the highly material world of the collector who doesn't collect for financial value (although many collectors lie to themselves by telling themselves that it's about value). Which is not to say that it's any kind of spiritual pursuit, but there is the sense with many collectors that they are engaging in a higher pursuit. And it's something that feels palpably true with Allen and his work, both of which are imbued with huge, quiet, humble passion, both rational and irrational.

|