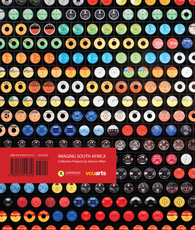

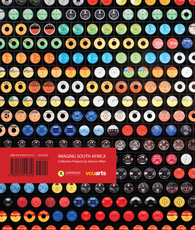

imaging south africa, catalogue, 2010

makeba!, anderson gallery, 2010

newspapers (wc), anderson galley, 2010

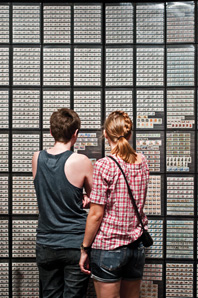

stamps v, anderson gallery, 2010

screen ii, anderson gallery, 2010

newspapers (wc), anderson gallery, 2010

vuvuzelas, anderson galley, 2010

screen ii, anderson gallery, 2010

stamps v, anderson gallery, 2010

stamps v, anderson gallery, 2010

makeba!, anderson gallery, 2010

makeba!, anderson gallery, 2010

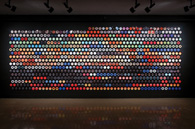

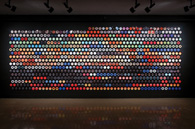

labels , anderson gallery, 2010

records, anderson gallery, 2010

records, anderson gallery, 2010

mirian make ba

, vmfa, 2010

newspapers (wc), anderson galley, 2010

stamps v, anderson galley, 2010

|

IMAGING SOUTH AFRICA: Collection Projects by Siemon Allen

Anderson Gallery Richmond, VA, USA

curated by Ashley Kistler

August 27 - October 31, 2010

Spanning all three floors of the gallery, this exhibition offered the most comprehensive presentation to date of South African artist Siemon Allen’s “collection projects.” Over the last decade, Allen has created expansive installations of various mass-produced ephemera—postal stamps, newspapers, audio recordings—that he has methodically acquired and catalogued. In terms of process, he approaches each project like an archivist, researching and assembling artifacts to disclose underlying narratives about their production, dissemination, use, and message. Allen employs the social critique that inevitably arises from his work as a means of interrogating what he describes as “the contradictory and complex nature of South African identity.”

The exhibition generated a catalogue featuring essays by Clive Kellner, Ashley Kistler and Andrés Mario Zervigon. The publication also included is an interview with Allen by Kistler and that text is reproduced below:

IN CONVERSATION

Ashley Kistler talks to Siemon Allen

(from Imaging South Africa, Anderson Gallery, VCUArts, Richmond, 2010)

Ashley Kistler: Let’s focus for a moment on the timing of your exhibition with regard to the events of this past summer—specifically the World Cup—and how that feeds so beautifully into your overall project, Imaging South Africa. Would you talk about why it was important for you to begin the show with the newspapers piece?

Siemon Allen: The newspapers piece has always been about how South Africa’s image is constructed in the US media. Previous displays featured varied topics with full articles and small random mentions. But as this version began to take shape, I realized that coverage of South Africa in the US press during this particular period of collecting was dominated by the country’s hosting of the World Cup Soccer. It seemed to me that it was an event that South Africa was using to rebrand itself. There are actually a couple of articles in The New York Times that talk about this event as a way to ‘reboot’ the country’s image. For most people, especially those who have never been there, South Africa has a very strongly defined image—most notably the apartheid years, the release of Nelson Mandela, the historic elections of 1994, subsequently followed by branding as a country of crime and AIDS. With the World Cup came the opportunity for the country to reassert itself not only in the press as a tourist destination, but also in pictures and stories that show another, more celebratory face.

As I examined the papers, I could see that soccer coverage was often not about what happened on the field, but rather addressed the social context of the game in South Africa, often in a noticeably positive manner. There were articles about the diversity of the fans and accounts of new conversations across racial barriers. There were stories from the past about the role of soccer among political prisoners on Robben Island, and from the present about the role of soccer among children in the townships, complete with images of handmade soccer balls.

So the larger newspaper collection has always dealt with this idea of imaging, and then there comes this moment in history when the country self-consciously talks about imaging. I thought this was an interesting opportunity to re-present that representation, if you like.

On a lighter note, so much of the coverage around the soccer dealt with the sound of the ubiquitous vuvuzelas. Perhaps this became the ultimate image of South Africa during this period. And so I decided to display two of these plastic horns from South Africa with the newspapers. During the World Cup, many vuvuzelas were decorated in countless ways—some with elaborate socks and others with more traditional means. One example on display features an elaborate beadwork cover, which was made by Rose Shozi, an artist working at the Hillcrest AIDS centre in KwaZulu Natal.

AK: What other considerations were most important to you in conceiving what work would go where on the three floors of this building, and also what the final form of each would be? The idea of installation as architectural intervention emerges once again as one overarching methodology.

SA: Oh, definitely. Let me begin with the woven videotape installation. I always saw that work as being conceptually part of the collection projects but just did not have the space to include it in my recent shows in South Africa. With this exhibition, there was the opportunity to link it to the other works. Something that goes back to many of my earlier pieces is the idea of the “room within the room.” It’s a display strategy that I’ve used for sometime now, and I am continually questioning what keeps drawing me back to it. I use to think it was somehow connected to my love for the “play within the play” in Hamlet, or that it was a way to make physical the metaphoric artificial space of a collection. All of the collections are displayed using some kind of architectural intervention, and each was a response to the particulars of the space.

AK: Talk a little more about how the form of each piece reinforces its content.

SA: One thing that I wanted to do was to somehow change that first room, where Newspapers is located, so that when you arrive at the Anderson Gallery, the augmentation of the space itself suggests something is different, something has shifted. The curved wall was also informed by earlier showings of my work in the grand cylindrical room at Durban Art Gallery and the Corcoran Museum’s Hemicycle Gallery. So I was already interested in the way the piece could curve and how I could work within the limits of the Anderson Gallery space. I extended the existing wall so that it became a more continuous, nearly quarter-circle that leads you into the woven piece, almost like a slide.

After this text-heavy introduction, your experience is sharply contrasted in the very next room where the reflective walls made with woven VHS tape are configured in such a way to form a space that is totally inaccessible. You are channeled into and around the space within the room but never allowed entry.

In the second-floor gallery, the Makeba records are displayed in a transparent curtain wall. The concave side of the curtain wall facing the entrance creates an overall cinematic view of the record covers and the viewer is able to move around the curtain freely. Most of the covers feature portraits of Makeba, and the effect is a grid with groupings of identical images and varied graphics. The convex side of the curtain wall creates a narrow passageway that allows for a more intimate reading of the extensive liner notes on the backs of the covers.

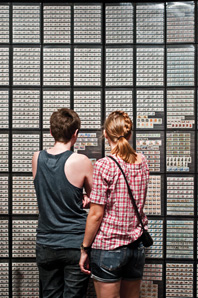

In the rectangular gallery on the third floor, the stamps are displayed on the interior concave surface of an oversized cylindrical structure. The circle of displayed stamps almost physically connects at the beginning and end points but is punctured by the entryway. In a way, these points do connect: the stamp collection begins in 1910—the year of the Union of South Africa—with a portrait of King George V. It ends in 2010 at the 100-year mark with a reissue of that very same stamp depicting King George V. Perhaps there is some irony in that!

I was interested in how the viewer would be confronted by the exterior wall of the stamp piece, and I hoped that it would bring to mind your initial experience of the inaccessibility of the woven piece downstairs.

So the projects throughout the Anderson space converse with each other. The curved newspaper wall is perhaps the most gentle intervention, compared to the others. The Makeba curtain is a light, almost transitory version of that same curve. The stamp-collection enclosure curves almost 360 degrees all the way around.

AK: When did this element of enclosed space begin to appear to in your work?

SA: I suppose the earliest version was the first sculpture I made after leaving art school. It was a small, intimate piece, where I reconstructed one of the many homes that I had lived in growing up. I placed what operated like a small wax model inside a display case. In a way, it was almost as if the house itself was a reliquary on display. For me, psychologically, the piece tackled issues around apartheid and this idea of protection—of living in a cocoon or a protected space—but also being on display. Perhaps with some uncanny prescience, the piece was titled The Collector.

In a way, you could almost say that a lot of what I’m doing today is an extension of these early display-case works. Those projects were very personal, and they came about at a very particular time in South African history, just prior to the ’94 elections. Perhaps they dealt with a form of latent self-critique. So they were a self-examination taking place from within South Africa at a specific period in the country’s history.

How that all extends into this work is a bit more complex, but I think one of the things that keeps coming up, especially with the stamp piece upstairs, is the idea of a laager. It’s a South African term from a time when the Boers were traveling overland with ox wagons. A common military strategy was to position these wagons into a circle—like a fort—so everyone on the inside was protected from the outside, so to speak. But what is curious is that this term is now used to describe a psychological state. A “laager mentality” is seen as a negative characteristic and suggests someone who is in a persistent state of isolation or fear, someone who is building psychological fences.

Ten years or so ago, Kendall [Buster]and I were in the leafy suburbs of Johannnesburg with a camera. I drove around a number of residential blocks while she filmed the walls in a continuous take. What was interesting was that you could go full circle around the block and, though there were perforations in the form of doorways, the walls surrounded the entire block; each was between ten and twelve feet high.

Screen, the impenetrable woven installation, is perhaps the most laager-like in my mind, though I do think all the pieces address it in some kind of way. The newspapers are like pasted posters on a wall. The stamp display, like Screen, most definitely references the laager but in this instance the viewer is able to gain access to its center and view its treasure. Ironically, once inside, the visual feast of this archive, stands in sharp contradiction to its veil of propaganda.

AK: The cylindrical container for the stamps is also initially inaccessible. It occupies the space in such a way that as viewers approach it through the first doorway, they discover it’s possible to go only so far around the piece until their path is blocked; they must then exit the room, walk down the hall, and enter at the opposite end to further experience the piece. How form influences content in these pieces also relates to the idea of concealing or revealing in terms of withholding information or making it accessible. Would you talk about how this operates in your work?

SA: Sure. The VHS videotape is an information carrier, but the information it carries in the work remains inaccessible to the viewer. And so inasmuch as you can’t access the physical space of the piece, you also can’t access the content of the piece.

Something I’ve been thinking about for a long time is how much the idea of inaccessible information resonates with my experience of growing up in South Africa. It was an environment that was very insular, and there was a great deal of censorship. As a teenager, I remember there were these windows into the wider news media: friends whose parents had traveled overseas brought back newspapers with images that would not appear in the South African media.

It may be less obvious how the woven piece fits into my collection projects but, like the other projects, which are constructed with printed materials, it contains information. However, the VHS weave is different because it allows one to speak about the power of silence. And every time I show the work, depending on the context, it evokes a different interpretation. For example, the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale in 1997 took place concurrently with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. Captivated by hours of viewing these live broadcasts, many people thought the videotape I used contained recordings from the TRC. At the same time, the spectacular funeral of Princess Diana occurred and, so for other viewers, the work was a monument to her. I guess for some the piece becomes a type of memorial and, in its current context here it could be viewed as an archive of the unseen in South Africa’s past.

AK: The notion of changing perspective is manifest in these works in so many ways. In terms of the viewer, it applies to perspective shifts that occur as you physically move around and through each piece, of course, but also to our mental inclination to project meaning onto the work when information is withheld, unseen and unheard.

SA: You see yourself reflected in the work. So I suppose from a psychological point of view you might ask if the content is the viewer contemplating his or her own reflection. Is it just a mirror image, or a blurred mirror image? There are levels of layering in the piece, but it is essentially, I suppose, a piece about nothing. But it can be so many things.

With the other installations, I am always interested in the tensions between the far view and the close view. The far view would be a panorama; the close view would bring the particular into focus. So there is a battle between the specificity of each artifact and the pull towards those items operating in the service of an organizing configuration that becomes a large visual field. This is true with Newspapers and Makeba!, but perhaps most complex with the Stamps, given the massiveness of the installation in counterpoint to the scale and number of units.

AK: With the current version of Stamps, I know the stamps are in chronological order, and they cover exactly 100 years. But in order to fill the entire cylinder, how did you plot out the entire configuration? How did you determine how many of these blues stamps to use, for example? Were those purely aesthetic decisions?

SA: When I realized that I had more stamps than I could display even in the large installation, I went through all the stamps before we started, and I counted how many I had of each. My goal was to index the final display to the actual number of each different stamp in the collection. So if I had 5,000 of one stamp and 4,000 of another, I wanted the display ratio to be 5 and 4. I wanted the installation to accurately reflect the percentages of stamps that were to some extent used historically; if the blue stamp was widely and commonly used, then the installation needed to reflect this. Of course the other goal was to show at least one of every stamp image—rather than being philatelically correct and showing every iteration of each stamp for color shifts and errors. Given this, stamps that are less common do not repeat as often in the display.

Interesting implications arise. For example, the stamps that predominate in the entire installation are from the Protea series, which came out in 1977. The Soweto uprisings occured in 1976, and Stephen Biko was murdered in 1977. Consequently, these stamps seem especially opaque and silent given this history. It’s interesting that they are so abundant, and that these particular flowers are quite hardy—I have heard of them referred to as “dinosaur flowers.” Almost a quarter of the installation is taken up by the proteas, which camouflage very tragic events.

When you come to the end of the display, there are almost no repetitions, probably because the stamps issued in the last ten years are pretty much all commemorative and targeted to a collector’s market. You can really see in the piece the rise of email and the concomitant decline of stamp usage. In appealing to this collector’s market, the function of the stamp has shifted. With the repetitions in the display, you see the extent of the stamps’ everyday usage, which ultimately culminates in self-conscious designs for collectors. I think that’s kind of interesting.

AK: Yes, it is. The more you talk about the piece, the more it becomes a feat of ingenuity—a complex installation on many different levels. Once this exhibition closes, Stamps will go to a permanent home in South Africa?

SA: Yes, I exhibited the piece in Durban, at the Durban Art Gallery in 2009; it was about half the size then and displayed in nine panels that were hinged together, to create a curved wall. I had met collector Gordon Schachat at the time through Clive Kellner, and he was very interested in the piece. He said he’d like to buy it, and asked how I would like to ideally display it. I recall saying right away that I wanted it to be more comprehensive and displayed in a full circle that encompassed the viewer. And that’s how this piece came about. Once the show closes, I plan on doing a final edit of the stamps displayed. After that it will go to the museum Gordon is building for his collection.

AK: In the wake of this completed project, the new prints suggest another direction for your work, even though they are dependent on your collecting activities.

SA: The prints were a way for me to return to art-making with a process that was very different from the collection projects, which involve amassing all this material, combining it, and re-presenting it. I felt I needed to get back to something more physical. Now you could say that scanning isn’t necessarily physical! But there’s something about selecting a record that has a particular kind of damage or label marking, scanning it in high detail, blowing up and then printing the scan on archival paper to create this iconic image. For me, this was a return to something vital. I don’t want to call it object-making. The result is an object, but it’s also an image—a singular image—rather than the grids of found, mechanically reproduced materials.

AK: What are you working on now?

SA: My next major project, an extension of Records, is a searchable web archive of the entire audio collection. You can view it at www. flatinternational.org. The site produces discographies every time you search for any particular term or artist, as well as detailed images showing the cover, liner notes, and label of whatever volume you select. Of course, it will only be as good as the data entered, and that will take a long time! But I feel like it’s the one thing I really want to do at the moment.

A number of great blogs such as Matsuli and Electric Jive already exist and some organizations like the South African Music Archive Project (SAMAP) have been working on something similar to what I have in mind, though funding is always an issue. The flatinternational website probably won’t be as dense as an officially supported project with staff, but I feel where it may differ is in the focus on a visual archive of this audio material—it is as much about the image, the artifact, and the liner notes as it is about the audio content.

August 2010

|